- Home

- Lauren Willig

The Summer Country Page 10

The Summer Country Read online

Page 10

“That’s a pity,” said Adam, who was roaming about the room with the air of a man who felt his time was being wasted. “I was hoping for a duel or an elopement at the least.”

“There were those, or so I’m told, but in previous generations. There’s a story—”

“Are you telling fairy stories, George?” A woman appeared at one of the arches, black taffeta rustling importantly as she stalked toward them. She was of medium height, a black lace cap on her gray-streaked brown hair. “Never mind my grandson. He spends too much time reading Sir Walter Scott and spinning pretty fancies for himself. Roundheads and Cavaliers, indeed!”

“But they were,” protested Mr. Davenant, unoffended. “You told me so yourself.”

“They were planters and Barbadians. All the rest is immaterial. We have a saying in these parts, ‘Neither Carib nor Creole, but true Barbadian.’ You, I take it, are not from these parts.”

Mr. Davenant looked apologetically at his guests. “May I have the honor of making you known to my grandmother, Mrs. Davenant? Grandmama, may I present your new neighbor? Miss Dawson has recently come into possession of Peverills.”

“Peverills?” Mrs. Davenant examined Emily with a concentrated interest reminiscent of Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf. “Welcome, indeed, then. Peverills has stood empty for so long, we had begun to despair of it.”

“It seems my grandfather bought it some time ago.” Some further explanation seemed to be required, so Emily added, “He came to England as a young man, but he always accounted himself a true Barbadian.”

“He was well-respected in Bristol,” Adam countered. He had never been comfortable with their West Indian origins, had winced away from their grandfather’s stories, making himself as English as English could be. “He might have been an alderman if he had wanted to be.”

Mrs. Davenant looked distinctly unimpressed. To Emily, she said, “And who might your grandfather be?”

“His name was Jonathan Fenty.” Was. That was felt like a knife in her chest. She didn’t quite believe it yet, that he was gone. “He left the island some years ago. I don’t imagine—”

“Jonathan Fenty.” Mrs. Davenant’s face looked like a mask, frozen into place. She lifted a lace-edged handkerchief, coughing delicately into it. “I knew him. Not to speak to, of course. He was bookkeeper at Peverills. And a Redleg.”

“A Redleg?” Laura looked inquisitively at Mr. Davenant.

Mr. Davenant’s color rose. “It’s a term for—for people who live in the area we call Scotland. They’re mostly of Scots and Irish origin. When they worked in the field, their, er, extremities would burn in the sun. Hence the term.”

“Dirt poor, the lot of them,” Mrs. Davenant said, so viciously that Emily half expected to see welts rise on her skin from the venom. “I don’t expect your grandfather ever spoke to you about where he came from.”

“My grandfather,” said Emily, “never made any pretense about his origins. He was proud to be a self-made man.”

“I understood he married a wealthy widow.”

“And made her wealthier by far.” Emily didn’t know what her grandfather had done to make Mrs. Davenant hate him so, but she refused to be intimidated. “My grandmother’s inheritance was modest compared to what my grandfather achieved.”

Not that her grandmother had ever gloried in wealth. She had been raised a Methodist, and, although she had come to the Church of England with her first marriage, the principles had remained. It had made Emily’s grandmother an admirable, if not always a comfortable, figure.

But they had been well-suited, her grandparents. Emily remembered her grandfather’s boyish glee at his wealth, and the way her grandmother humored him—and continued to oversee the mending. For that, her grandfather had been equally parsimonious about small things. It was only in the large things that he tended to display, buying jewels her grandmother would never wear and waistcoats so heavily embroidered with gold and silver that they could light the way for passing ships.

Mrs. Davenant examined Emily so intently that Emily’s nose began to itch. “You loved him.”

“He was my grandfather.” Her grandfather and the one person she could trust, always, to put her interests first. Emily swallowed hard against a sudden rush of grief. “I would trade my inheritance in a moment to have him here with us again.”

“Now here’s a pattern of filial devotion for you.” Mrs. Davenant turned away with a rustle of starched linen and horsehair. Emily could almost hear everyone begin to breathe again. “Not everyone feels quite so warmly about their grandparents, eh, George?”

Mr. Davenant wrinkled his nose. “Grandmama . . .”

“Don’t write me any poems.” Mrs. Davenant stalked over to Adam, peering at him through the lenses of her lorgnette. “I don’t need to ask whether you’re a Fenty. You have the look of your grandfather.”

“Sunburnt and penniless?” Adam tried to make a joke of it, but it fell flat. “I can only endeavor to follow my grandfather’s example in the leadership of Fenty and Company.”

“Fenty and Company.” Mrs. Davenant rolled the words on her tongue as though tasting something unpleasant. “How times have changed. And is Peverills now the property of Fenty and Company?”

“No,” said Emily. She felt as though a game were being played to rules she didn’t understand, with her family the butt of it. “Peverills is mine and mine alone.”

To her surprise, Mrs. Davenant lowered her lorgnette. “Hold to that, Miss . . .”

“Dawson,” supplied Mr. Davenant.

“Miss Dawson. There will be many who will try to tell you otherwise.” Without waiting for an answer, she turned on her heel and stalked toward the dining room. “I imagine you expect to be fed?”

Laura looked imploringly at Mr. Davenant. “We don’t wish to be any bother. . . .”

“It’s no bother at all,” said Mr. Davenant gallantly.

“George! You take in Miss Dawson. Mr. Fenty”— Mrs. Davenant eyed Adam with distaste—“your arm, if you please.”

Mr. Davenant bowed to Emily. “If you would do me the honor?”

Emily began to think that Dr. Braithwaite had made the right choice in leaving; she would have been glad to decline. But they had no way back to Bridgetown but Mrs. Davenant’s carriage, so she took his arm and said, “Thank you. We didn’t mean to put you out.”

“You haven’t,” said Mrs. Davenant, going unerringly to the head of the table. “The table is uneven. We’re short a man.”

They would have had an even number had Dr. Braithwaite stayed.

Mr. Davenant held out Emily’s chair for her, a tall affair with spindly finials and a back made of cane. She sat gingerly, glancing around the table, uncomfortably aware of the contrast between those seated at the mahogany board and the servants positioned around the table.

Would Dr. Braithwaite have been invited to sit at this table, to share this board? Or would he have been snubbed, turned away?

“Pepper pot, Miss Dawson?” A footman was holding a tureen extended in front of her, a savory blend of meat and some sort of vegetable.

“Oh yes, please. Thank you,” said Emily to the footman, who continued to look straight ahead. Of course he did. Aunt Millicent would never have countenanced any of her servants speaking to the guests. Emily ducked her head to her plate. “What is pepper pot?”

“I suppose you might call it . . . a stew? Do try some, Mr. Fenty,” urged Mrs. Davenant. “It is one of our local delicacies.”

“Delicious,” gasped Adam as tears formed in the corners of his eyes.

“You might want to try it with bread,” murmured Mr. Davenant to Emily, who nodded her thanks and took a large piece to sop the sauce. Laura, Emily noticed, had gingerly taken a bite.

“If you come again,” Mrs. Davenant was saying to Adam, “we’ll give you calipash and calipee.”

“Turtle,” explained Mr. Davenant, leaning sideways to Emily. “Well . . . part of the turtle. The squishy bit

beneath the shell.”

“Thank you, George,” said Mrs. Davenant. “Did your grandfather explain nothing to you, Miss Dawson?”

Not about turtles, certainly. “We never had pepper pot. Or—calliope?” She looked inquisitively at Mr. Davenant.

“Calipash,” he provided for her.

“And what did he tell you of Peverills?” Mrs. Davenant was looking at her with that disconcerting directness.

“Nothing at all.” Emily surreptitiously gulped down half her glass of lemonade, trying not to pant too obviously. She would have suspected that the pepper pot had been served by way of trial by fire but for the fact that both Mr. and Mrs. Davenant were eating the dish with obvious relish.

“Did he tell you that Peverills belonged to the Davenants?” persisted Mrs. Davenant.

“Until we lost it,” put in Mr. Davenant.

“You make it sound as though we misplaced it,” retorted Mrs. Davenant. “It was mismanagement, pure and simple. The estate was run into the ground. The Davenants were decorative, I’ll give them that, but they didn’t have the slightest idea how to operate a plantation.”

Mr. Davenant helped himself to more pepper pot from the dish held by a silent servant. “What about Grandfather?”

“What makes you think he was any better? He tried, I’ll give him that. The damage had already been done. He meant well,” she said grudgingly. To her grandson, she added, “You’ll do better. I’ve had the training of you.”

“With rigor,” said Mr. Davenant.

Emily drained her lemonade and set her fork aside. “Might I trouble you for some of that training? I would be grateful for any advice.”

Adam gave a little cough. “You don’t want to bother Mrs. Davenant with all that. I’m sure her agent . . .”

Mrs. Davenant fixed him with a basilisk stare. “I am my own agent. Agent and estate manager and court of last resort. I gave up on hiring help. They were sots, most of them, more interested in the bottle than their work. Of course, there’s George,” she said, dismissing her grandson with a wave of a heavily incised silver fork. “But he’s much to learn yet. You want to know anything about sugar, you ask me.”

“I want to know everything about sugar,” said Emily frankly. “I know about the use of it, but nothing about its cultivation.”

“You’ll have to if you want to keep Peverills,” said Mrs. Davenant.

“You can’t possibly—” Adam began, but Mrs. Davenant went on as though he hadn’t spoken.

“You could hire someone to manage it for you, of course, but there’s no guarantee he won’t rob you blind. In fact, it’s quite likely anyone you hire would. They’ll have your measure in a minute: a woman. English. Absentee.”

“And utterly ignorant,” added Emily.

“Exactly,” said Mrs. Davenant approvingly. “You might as well sign the estate over now.”

“And,” said Emily, “I imagine it would cost money to hire an agent—a good one. And I haven’t any at present. Money, that is.”

Adam winced. “Surely this isn’t a proper subject for—”

“Land poor, are you?” Mrs. Davenant leaned both elbows on the table, her diamond earrings glittering in the light. “That’s nothing of which to be ashamed—although I find it strange in Jonathan Fenty’s granddaughter. I heard your grandfather was a warm man.”

“My grandfather knew I could be trusted to make my own way.”

Mrs. Davenant snorted. “I’d hardly call inheriting Peverills making your own way. You’re an heiress, girl, whether you like it or not.”

“The house . . .” put in Adam.

“Eh.” Mrs. Davenant waved that aside. “A house is a house is a house. The land is rich, always has been. Those Peverills knew what they were doing when they staked their claim to those acres. It won’t take much to put it right again. But it will take money. Money for equipment, money for hands. You haven’t any jewels to sell, have you?”

Emily touched the plain oval locket at her throat, the other half of her legacy from her grandfather, worth less in coin but twice as valuable. “I could borrow the money, couldn’t I? With the plantation as security.”

“You could,” said Mrs. Davenant. “If you want to lose it. You can’t trust those moneylenders. Leeches, all of them. They’ll suck the life out of you and then take your land once you’ve been bled dry. I’ve seen it happen before. I have a better suggestion for you. Sell me the southeast parcel. Use the money from that to cultivate the rest.”

“Or you could just sell the whole thing,” offered Adam, “and come back to Bristol.”

To sit in Aunt Millicent’s parlor and wind wool? Emily couldn’t think of anything she would like less. To Mrs. Davenant, she said, carefully, “I wouldn’t want to alienate any of the land until I had a better sense of the workings of the whole.”

“Right now, the whole is rotting,” said Mrs. Davenant. “And will continue to do so unless you expend some considerable funds. Would you consider leasing the parcel?”

“I would have to consult my agent in Bridgetown.” That is, if she had an agent in Bridgetown. Mr. Turner, she knew, had served as her grandfather’s agent in any matter of things, but that arrangement wouldn’t necessarily extend to her. It would, however, give her an excuse to return to the Turner household. She wondered if Dr. Braithwaite would be in residence.

“Agents.” Mrs. Davenant dismissed the breed with a tilt of her glass. She was drinking claret, not lemonade, although Emily noticed she only sipped sparingly. “In my day, such matters were dealt with between gentlemen.”

“As we are?” said Emily, rather liking the notion. “There’s just one problem. I don’t know enough to even begin to discuss terms.”

“Ah, well. It was worth an attempt,” said Mrs. Davenant, unabashed. She raised her glass to Emily. “That’s the first challenge. Admitting what you don’t know. You would be surprised at how few can manage it.” She looked pointedly at her grandson, who pulled a face in response.

Emily did her best to swallow her smile. “I am very sensible of my ignorance. But I’m a quick study.”

“Speak to your agent. I’m sure we can come to an arrangement.” Mrs. Davenant stood, abruptly signaling the end of the meal. “George, why don’t you show Mr. and Mrs. Fenty our garden. There are views clear to the ocean if you stand in the right spot. Miss Dawson, you’ll come with me.”

Adam looked over his shoulder in surprise as his chair was magically pulled back for him. Saving face, he said importantly, “We do have an evening engagement in Bridgetown. At the governor’s house.”

“Those are always a sad crush. That Colebrooke sends a card to every stray who wanders off the wharves.” Having rendered Adam speechless, Mrs. Davenant added magnanimously, “Don’t worry. I’ll get her back to you in plenty of time. Go along now.”

“The gardens are lovely,” said Mr. Davenant. Emily began to understand why he so frequently sounded as though he were apologizing. He was in the habit of it. Taking charge of Laura and Adam, he led them through yet another arch in the middle of the far wall. “Do you sketch, Mrs. Fenty?”

Mrs. Davenant took Emily by the arm, marching her in the other direction, back through the great room. “You have to be direct with men. They have no truck with subtleties. You don’t favor your grandfather.”

Emily was beginning to get used to her abrupt changes of topic. “I look very like my father.”

Mrs. Davenant eyed her sideways, taking the measure of her features, the soft, mid-brown hair, the hazel eyes that were more brown than green. “Is he also from Barbados?”

“Yorkshire.” It was strange how exotic it sounded here, in this large, light-filled room. The moors and mists of her father’s childhood home might have been something out of a novel by Currer Bell. “But my father has served for some years as the minister of a parish in Bristol.”

A very poor parish in Bristol. That had been by choice, not chance. Her father’s convictions would suffer nothing more. Had n

ot the Lord himself gone among the poor? Although sometimes Emily suspected it was less a matter of conviction and more that her father simply didn’t notice such things. He would eat mutton as happily as beef.

Her grandfather had raged at his daughter throwing herself away on a penniless clergyman, a clergyman, no less, with no ambition for the higher orders, content to serve in the poorest section of the city. But her mother had never wavered. It was a story Emily had loved to hear as a child, how her mother had held fast in the face of all opposition.

“And what does the Reverend Mr. Dawson think of his daughter gadding halfway across the world?”

“He gave me his blessing.” Never mind that her father’s blessings were extended easily and broadly. And that he had, now, other interests. No, she wouldn’t think about that. Not now. Not here. “He raised me to know my own mind.”

Mrs. Davenant emitted a distinctly unladylike snort. “No one really expects a woman to know her own mind. You’ll find that out soon enough if you try to take Peverills in hand. Every man jack of them in Bridgetown will pat you on the head and try to make your decisions for you.”

They had stopped at the end of the great room, where a rectangular opening led into a small room containing several beautifully made bookshelves and a tall and narrow desk bristling with pigeonholes.

Emily looked at Mrs. Davenant, imposing and imperious in black taffeta. It was impossible to imagine her being patted on the head, at least not if the offending party wanted to keep his hand. “But you managed it.”

“I married.” Something about the way she said it forbade further comment. “What are you doing standing there? Come into my office. Oh yes, this is my office. I send George out to supervise the day-to-day running of the thing, but all the paperwork comes back to me.”

Not just the paperwork. There was, Emily saw, a door that led to the veranda, a private entrance. And, next to it, a spyglass on a brass stand.

“It’s good for him to ride the length of the land,” Mrs. Davenant was saying. “I know every inch of my land; I know it in my bones. Do you ride, Miss Dawson?”

That Summer

That Summer The Mischief of the Mistletoe

The Mischief of the Mistletoe The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla

The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla The Other Daughter

The Other Daughter The Ashford Affair

The Ashford Affair The Lure of the Moonflower

The Lure of the Moonflower The Secret History of the Pink Carnation

The Secret History of the Pink Carnation The Masque of the Black Tulip

The Masque of the Black Tulip The Passion of the Purple Plumeria

The Passion of the Purple Plumeria The English Wife

The English Wife The Garden Intrigue

The Garden Intrigue Ivy and Intrigue: A Very Selwick Christmas

Ivy and Intrigue: A Very Selwick Christmas The Orchid Affair

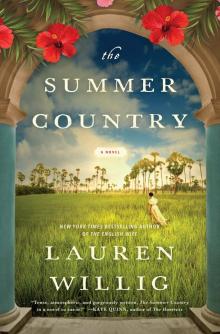

The Orchid Affair The Summer Country

The Summer Country The Betrayal of the Blood Lily

The Betrayal of the Blood Lily The English Wife: A Novel

The English Wife: A Novel Masque of the Black Tulip pc-2

Masque of the Black Tulip pc-2 The Secret History of the Pink Carnation pc-1

The Secret History of the Pink Carnation pc-1 That Summer: A Novel

That Summer: A Novel The Mischief of the Mistletoe: A Pink Carnation Christmas

The Mischief of the Mistletoe: A Pink Carnation Christmas