- Home

- Lauren Willig

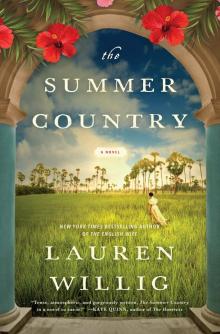

The Summer Country Page 21

The Summer Country Read online

Page 21

“And you in the middle of it?” said Charles. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. I had thought if they were happy together—”

“Then we might be too?” There was something so wistful, so vulnerable in the words. It made Charles want to ford oceans and slay dragons for her. Surely, this should be simple in comparison?

“We will be. We’ll find a way.” Charles wrapped his arms around her, feeling, for the first time in a very long while, as though he’d come home. Which was foolish, since he hadn’t been anywhere. She was the one who had gone away. But there it was. “Perhaps once there’s a child . . .”

“That may be sooner than you think. Mary Anne’s been ill two mornings now.”

“But that’s of all things wonderful!” Charles said, sitting up straight. “Robert will be pleased, I imagine. He’ll have proved his virility and secured an heir. And as for your mistress . . .”

“It will give her someone else to manage?” Jenny finished for him.

Charles felt seized by a sudden surge of optimism. He squeezed Jenny’s hands. “You’ll see. We’ll have it all sorted and you at Peverills by Christmas.”

“If you say so,” said Jenny skeptically.

“We’ll make it so.” Nothing could fright him out of his good humor now, not with Jenny home again. “You’ll see. Jack shall have Jill and naught shall go ill.”

“Until you fall down and break your crown.”

“But will you come tumbling after?” Charles kissed her. “There’ll be no breaks and tumbles. Once Robert’s baby comes, they’ll be too pleased with themselves to waste any time on the likes of us. They’ll scarce remember we exist.”

Chapter Fifteen

Christ Church, Barbados

May 1854

“I had no idea you had an uncle Charles,” said Emily. “No one ever mentioned him.”

George discovered a deep interest in the backs of his gloves. “Well, they wouldn’t. He’s been gone for some time now. And my grandmother rather minded his selling Peverills.”

It wasn’t just that, thought Emily, looking at George’s averted face. Mrs. Davenant had gone to some trouble to create the impression that Peverills had been unfairly wrenched from her hands in some hole-and-corner fashion. When, in fact, it had never been hers to begin with. All of it, the paired portraits on the wall, the grand pronouncements, were, if not a lie, then at least a substantial misrepresentation.

“If your grandmother was never mistress of Peverills,” said Emily, “then how did she come to have the account books?”

“I wasn’t born yet,” George prevaricated, “but as I understand it . . . the books were left in the bookkeeper’s house, and my grandmother thought it best—that is, she took it upon herself to . . . um, to watch over them for Uncle Charles. While he was away.”

In other words, she had stolen them. “I see,” said Emily.

“It was all in the family,” Mr. Davenant hastened to explain. “Uncle Charles seemed disinclined to marry, so it was expected the estate would come to my father eventually. No one ever expected that he might sell it.”

“But why would he go away just like that?” Emily looked out over the blackened gables of Peverills. True, the house was ruined, but there was still the rest of the plantation. If her grandfather had bought the plantation twenty-odd years ago, that still left twenty years that the land had been left untenanted, abandoned. “Even if one hadn’t the money to rebuild, he might have gone on farming the land and lived in the bookkeeper’s house. Or leased the land to someone else. Why leave it all sitting empty like that?”

George glanced at her sideways. “The story I was told was that it was because of the little girl. His ward.”

“His who?”

“I forget you don’t know. It’s all common knowledge here. Well, legend, really. I’m not sure how much is true and how much pure embellishment, but . . . I’m not telling it very well, am I?”

It seemed churlish to agree, so Emily tilted her head at an expectant angle and waited.

“My grandmother doesn’t talk about any of this,” George said seriously. “I had it from the servants, and the stories do tend to vary rather wildly. But if you boil it all down, it comes to this. My uncle had a ward, a little Portuguese girl. This was during the wars with Napoléon, you know.”

Emily nodded. “They went on for some time.”

“We’re rather proud of our part in it all here,” said George. “In any event, the girl was the child of a schoolmate who died on the peninsula. My uncle was very sincerely attached to her, I gather.”

Emily remembered the doll lying in the grass, the paint blistered and faded. “What happened to her?”

“She died in the fire.”

Emily had expected as much, but to hear it made it more stark, more real. “How dreadful. That poor little girl.”

“Uncle Charles was devastated. He’d promised his friend he’d see her safe, and . . .” As one, they both looked out at the fire-blasted stone and fallen rubble. George’s Adam’s apple bobbed up and down beneath his loosely tied stock. “Can you imagine that? To have made it through a war safely and then to die like this?”

Emily shook her head mutely, trying not to imagine that little girl as she must have been, nearly half a century ago.

“I know such things happen all the time,” said George, “that there are fires and children die in them, but this was on our own doorstep, as it were.”

Emily looked up at him, her eyes meeting his. “Just because it happens all the time doesn’t make it any easier.”

“They say she haunts the place, that if you come here after dark, you can hear a child crying, calling out for help that never comes.”

There was something about the way George said it that gave Emily a rather shivery feeling, despite the heat of the day.

“What was her name? The little girl?”

George blinked at her. “Do you know, I don’t know? Something foreign, I imagine. My grandmother only ever called her the Portuguese ward, so that’s how I think of her. The Portuguese ward.”

“Is there no grave?” It seemed terribly wrong that a child should die and be remembered as nothing more than a cry in the night, remembered only for the manner of her death and not her brief life.

“I don’t believe they ever recovered enough to bury. The fire smoldered for days, my grandmother said. People were afraid to go near it. And by the time they did . . . So many people died in the blaze, and it was all such a muddle, that they never did quite find all the pieces of everyone who was missing. There had been a number of house servants in the building, you see, and some of them had visitors, and . . . well.” George grimaced at her. “What a grim topic for a beautiful day. I’m sorry. I didn’t follow you out here to regale you with horrors.”

“I’m glad to know,” said Emily slowly. “It makes it all—not make sense, precisely, but at least I know now why the plantation was sold.”

“If you believe the story,” said George.

“Do you?”

He thought for a moment. “Yes. I do. My uncle—no one ever speaks much about him, but I gather he had grand plans for Peverills, for reforms and model farms and all that sort of thing. Whatever happened had to be truly wrenching for him to give all that up—and break all ties.”

He sounded a bit wistful. “Have you ever wanted to just disappear?” asked Emily curiously.

George smiled a lopsided smile. “Constantly. Haven’t you?”

“No.” Emily felt a pang of fierce longing for the world she had left, for her grandfather’s study at twilight, with the lamps just lit; for Laura’s room at Miss Blackwell’s, where Laura would read or dream while Emily sewed; for her work at the hospital, where Adam would appear out of nowhere to swoop her off for drives in his new curricle. She missed the life she had built for herself, that busy, useful life. “Where would you go?”

“Rome, perhaps,” said George dreamily, “to wander the Colosseum and sketch statues. Or maybe S

witzerland to gaze up at the hills and paint my reflection in mountain streams.”

“Not Paris?”

“My father is in Paris.” George shook himself out of his reverie. “It’s just a dream, of course. I’d never go, not really. There’s too much to be done here. Shall we go back?”

“I’ve only just got here,” said Emily. “I’d wanted to see more of the estate.”

“It’s mostly dead fields,” said George. “There are some tricky bits toward the east—caverns and ravines as you near the water. You wouldn’t want to go there without a guide.”

Emily remembered Dr. Braithwaite’s warnings. “Are you volunteering?”

“If you’d like.”

“Don’t worry, I didn’t intend adventuring that far,” said Emily, amused despite herself at his obvious lack of enthusiasm. “Just to the bookkeeper’s house.”

“Oh,” said George. And then, “Why?”

“Why wouldn’t I? It’s mine now, isn’t it?”

“It’s nothing much to see,” said George. “Just a house, and not a particularly grand one.”

Emily looked up at him curiously, wondering what it was that made him so reluctant to show her that particular corner of the estate. “My grandfather lived there once. I’m curious to see the place that was once his home.”

Before he was accused, if Mrs. Poole was to be believed, of sending it all up in flame. But no. She couldn’t possibly believe that. It was just malicious gossip, the vicious slanders of those who resented that a poor boy had made good.

“All right,” said George reluctantly. “It’s not far. But you should know . . . it may not be entirely unoccupied.”

“No?” Emily had to concentrate on her footing; what had once been a walkway leading around the house was now crumbled and cracked, roots stretching across to trip the unwary. George offered her his arm as she stumbled. “Thank you. But what do you—oh.”

In front of a plain, white-walled house waited a good dozen people, some sitting on the ground, others leaning against the wall of the house. There was a man with a makeshift bandage around his arm and a woman with a child on her back and another in her arms. Three children played a game that involved running back and forth, adding to the din.

They all fell silent as Emily and George approached, and in the sudden silence Emily recognized her own maid Katy, holding a child of two or three, who locked her arms around Katy’s neck and buried her head in her shoulder as Emily raised a hand in uncertain greeting.

“Hello?” said Emily, feeling rather as though she’d intruded. She smiled at the little girl. “Good morning.”

The little girl ducked her head again. A sister? A daughter? Emily realized with shame that she didn’t know and had never asked.

“Is the doctor in?” asked George, a slight edge to his otherwise pleasant voice.

The man nearest the door nodded. He was holding one hand over a bandage stained with red on his right arm.

“How did you come by that, Elijah? Did Ruth come after you with a hoe?”

There was an uneasy laugh all around. “Knife slipped,” said Elijah.

“And you came all this way to have it looked at?”

No one answered.

“All right, then,” said George. “You don’t mind if we slip ahead, do you? We won’t keep the doctor long.”

“Oh.” Emily paused as realization dawned, remembering the last time she had seen Dr. Braithwaite, the words that had passed between them. Slowly, she followed behind George. “Is this . . . ?”

“Yes,” said George, leading her ahead of the waiting patients. “Welcome to Nathaniel’s illegal infirmary.”

He spoke loudly enough that his words preceded them into the room, which had been turned into a makeshift operating theater. A man lay on a well-scrubbed table, flesh gaping from a nasty gash down his leg. Beside him, Dr. Braithwaite was engaged in stitching the wound together. A bowl sat on the floor beside him, filled with reddish water and stained cloths.

“Hardly illegal,” said Dr. Braithwaite, without looking up from his work. His stock was neatly tied, his waistcoat of the first quality, but he had stripped to his shirtsleeves, the cuffs folded back to bare his forearms.

“You’re trespassing,” said George, looking away from the wound.

“Have you come to evict me?” Dr. Braithwaite reached for a pair of scissors. Without stopping to think, Emily leaned forward and placed them in his hand.

“Thank you, Miss Dawson.” He looked up and their eyes met.

Emily found herself struggling to find something to say, but her mind was blank.

“If you’re planning to assist, you might wash your hands first. You’ll find fresh water on the bureau.”

“Surely, you’re not going to . . .” protested George.

“Wash hands?” said Dr. Braithwaite, deliberately misunderstanding him. “I know a Viennese physician who swears it saves lives. It’s a simple enough precaution to take. If there’s no value in it, I lose nothing by it.”

“Except the cost of the soap,” muttered George.

Ignoring George, Emily went to the bureau where there was, as promised, a bowl of water and a cake of soap. Despite the heat of the day, a fire burned on a camp stove, a kettle on the boil.

Wrapping a cloth around her hand to protect it from the handle, Emily lifted the kettle off the hook and poured boiling water into the bowl. The soap smelled strongly of lye. It bit at her skin with the force of memory.

“You didn’t mention that you were running your clinic on my land,” said Emily as she dried her hands on a cloth.

“I could hardly run it on Beckles land,” said Dr. Braithwaite. He glanced up at George. “Could I.”

George looked uncomfortable. “Beckles has a physician.”

“No, it hasn’t,” said Dr. Braithwaite. “If MacAndrews has any kind of medical training, I’ll eat my hat.”

“He attended the University of St. Andrews,” said George, without conviction.

“When they were still balancing the humors?” said Dr. Braithwaite, snipping off a thread. “Bandage.”

Emily handed him a roll of bandages. “Are you a physician or a surgeon?” she asked, more to change the topic than anything else. As she knew from her time in the hospital in Bristol, only physicians, who assessed and prescribed, were allowed to style themselves doctor. Surgeons, who dealt with the body itself, were mere misters. “Your uncle called you doctor, but . . .”

“Both. On the whole, I find my surgical training the more useful. My uncle, on the other hand, prefers the prestige of the higher degree. You can call me what you will.” Dr. Braithwaite tied off the bandage with an expert twist. “There. Keep your leg out of the way of your machete in future.”

“Do you sew up a lot of legs?”

“A fair few.” Dr. Braithwaite glanced sideways at George as he helped the patient off the table. “It’s preferable to lopping them off. Or leaving them until they fester.”

Sensing strife, Emily jumped in. “What sorts of ailments do you see? Other than legs, I mean.”

“Arms, torsos, scalps.” At her look, he began ticking off diseases. “Dropsy, lesions, night blindness, toothache, palsy. On the whole, malnutrition.”

George, leaning against the wall, stood up straighter. “We don’t starve our workers at Beckles.”

Dr. Braithwaite dumped Emily’s wash water into a bucket, refilling the bowl from the kettle. “No one said you did. But they hardly receive a varied diet. In case you didn’t notice, there’s a drought on.”

Emily hadn’t noticed. “There is?”

“Well, yes,” admitted George. “We rely on the rainy season, and this year the rains just weren’t . . . well, rainy enough.”

“Well said,” said Dr. Braithwaite drily, plunging his hands into the steaming water and soaping them briskly.

“But we’re surrounded by water,” said Emily. “Can’t one irrigate?”

“With saltwater?” Dr. Braithwaite

shook his hands, looking about for the cloth. Emily handed it to him.

“We’ve brought in more corn,” said George defensively.

“As I said,” said Dr. Braithwaite. “Would you eat corn three meals a day?”

“George,” said Emily, “is there a well? Would you mind fetching more water? That is, if there is any in it.”

“There is,” said Dr. Braithwaite. “Peverills has fewer demands on its water supply.”

George looked as though he intended to argue, but, instead, he said reluctantly, “I’ll have Jonah see to it.”

He left the door open behind him. Through it, Emily could see that the yard, which had been full, was now deserted.

“Oh dear,” she said, as George made his way across the yard to Jonah and the horses. “I hope we didn’t scare away your patients.”

“You did,” said Dr. Braithwaite.

So much for polite nothings.

“Why did you set up your clinic here?” Emily demanded.

“This house,” said Dr. Braithwaite, applying a wet cloth to the table, “was conveniently unoccupied. And, as previously noted, there is a well.”

“Oh, here, let me. You’re only making it worse.” Emily took the cloth from him, vigorously scrubbing at a bit of half-dried blood. “I mean, why Beckles? I’m sure there would be many other plantations where your services would be more welcome?”

“Are you?” said Dr. Braithwaite, holding out his hands for her to inspect. He let them drop to his sides. “Would you believe me if I said I did it to annoy Mrs. Davenant?”

“No,” said Emily. She thought of those endless teas, the promises Mrs. Davenant had made and hadn’t kept. “Although I understand the impulse.”

“Like that, is it?”

“She’s been a very welcoming hostess,” said Emily primly. “You didn’t answer my question.”

Dr. Braithwaite twitched the cloth away from her, dropping it into the slop bucket. “If you must know, MacAndrews killed my father.” As Emily stared at him, he shook his head, as though impatient with himself. “Oh, he didn’t take a cutlass to him. But he killed him all the same. My father cut his hand. A smaller cut than the one you saw just now. MacAndrews decided to amputate. My father died.”

That Summer

That Summer The Mischief of the Mistletoe

The Mischief of the Mistletoe The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla

The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla The Other Daughter

The Other Daughter The Ashford Affair

The Ashford Affair The Lure of the Moonflower

The Lure of the Moonflower The Secret History of the Pink Carnation

The Secret History of the Pink Carnation The Masque of the Black Tulip

The Masque of the Black Tulip The Passion of the Purple Plumeria

The Passion of the Purple Plumeria The English Wife

The English Wife The Garden Intrigue

The Garden Intrigue Ivy and Intrigue: A Very Selwick Christmas

Ivy and Intrigue: A Very Selwick Christmas The Orchid Affair

The Orchid Affair The Summer Country

The Summer Country The Betrayal of the Blood Lily

The Betrayal of the Blood Lily The English Wife: A Novel

The English Wife: A Novel Masque of the Black Tulip pc-2

Masque of the Black Tulip pc-2 The Secret History of the Pink Carnation pc-1

The Secret History of the Pink Carnation pc-1 That Summer: A Novel

That Summer: A Novel The Mischief of the Mistletoe: A Pink Carnation Christmas

The Mischief of the Mistletoe: A Pink Carnation Christmas