- Home

- Lauren Willig

The Summer Country Page 7

The Summer Country Read online

Page 7

“Not in the slightest. I could hardly leave you stranded here among these bare, ruined choirs.”

Laura ducked her dark head. “I was thinking more Time will rust the sharpest sword / Time will consume the strongest cord.”

It wasn’t time but fire that had consumed Peverills. Emily opened her mouth to say so, but Mr. Davenant got there first. “Marmion?”

“Marmi-what?” said Adam.

Laura shook her head. “It is Sir Walter Scott but not Marmion. Have you read Harold the Dauntless?”

“You have the advantage of me. Our library isn’t as extensive, but I can, at least, claim to have committed those works we have to memory. Are you acquainted with The Lay of the Last Minstrel?”

Laura’s cheeks pinked with pleasure. “Breathes there the man, with soul so dead, / Who never to himself hath said, / This is my own, my native land!”

“Your native land is Great George Street,” muttered Adam, shoving his hands in his pockets.

Taking advantage of Laura’s distraction, Emily took Adam by the arm. “If you will pardon us for a moment?”

“Do you intend to recite poetry at me?” said her cousin crossly, one eye on his wife. “Or do you mean to read me a lecture?”

“Neither. Did Grandfather ever say anything to Uncle Archie about . . . ?” Emily waved toward the smoke-blackened gables behind them. “About this place?”

“His own, his native land?” said Adam, but subsided as Emily fixed him with her best governess look. “You were there that day. Father was as surprised as the rest of us. If Grandfather were going to tell anyone, Em, it would have been you. You know that.”

“But?” said Emily. Her cousin had always had all the subterfuge of a golden retriever.

Adam scuffed at the gravel with the toe of his boot. “Father did say that Grandfather worked as a bookkeeper on a plantation. Before he met Grandmother.”

Emily looked up sharply. “Here?”

“It’s the most likely answer, isn’t it? It would be like him to take a fancy to own it.”

“And let it sit empty?”

“Maybe. He was never exactly forthcoming about his life in Barbados, was he?”

“He was about some things,” Emily said, in their grandfather’s defense.

“Yes, the morality tales. Hoeing the ground in the hot sun, trying to grow enough Indian corn to keep body and soul together, a fourteen-mile walk in blazing heat to and from the market in Speightstown. . . . We all heard those stories. But the rest of it? Who knows. Maybe he . . .”

“What?” The tips of Adam’s ears had turned red, a sure sign of guilt.

“Not fit for your ears, coz.”

“You needn’t go all prunes and prisms on me, Adam. I’m not”—she’d almost said “Laura”—“one of your sisters. There’s no need to spare my sensibilities.”

The gap between her father’s parish in St. Jude’s and her cousin’s grand house on Great George Street existed in more than just geography. There were times, at Miss Blackwell’s, when Emily felt a world away from her classmates, divided by what she had seen and heard. Adam’s sisters, she knew, understood it only as a matter of physical want; they made baskets and gathered up old clothes for Emily to deliver to “her” poor. Laura worried about their spirits; she put in impracticalities for them: sachets of fine linen and lavender, slim books of poetry, the items that she would want in times of duress.

But Adam, Emily thought, should know better. Or did he? He might have the run of the city, but he had never once visited her father’s parish, never seen the children playing shoeless in the gutter, the women who knocked at the kitchen door late in the night, shawls covering their bruised eyes.

Adam cast a glance over his shoulder, made sure no one was listening. “All right, then. The governor had a notion that Grandfather did something dodgy, and that was why he ran when he did—and why he had enough money to set himself up after.”

That, Emily was sure, was a distinctly abridged version. “Do you mean . . . he stole something?”

“Stole, reclaimed . . .” Adam made a helpless gesture. “A long time ago, Grandfather told me land was stolen from our family. He said the Fentys were lured to Barbados on the promise of land for work, that they had the work but never got the land.”

“This land?”

Adam shrugged. “You know as much of it as I.”

“So maybe that’s what this was all about. He wanted the land. It would suit him, to even the score.” Her grandfather was a firm believer in an eye for an eye. He wouldn’t take only the eye, but the spectacles as well, as interest. But something didn’t quite make sense. “Why leave it to me, then? I’m not a Fenty.”

“Once you’re sending plagues . . . Don’t look at me like that! I didn’t mean it. He always said you were the most like him of the lot of us. Maybe that’s why.” Before Emily could feel too pleased by that, Adam added, “And he did always feel that you’d got the short end of the stick, losing your mother and all. Remember when he used to bring out the bag of sweets?”

“One for you and two for me.” The memory made Emily smile, despite herself. Her grandfather, with that crumpled paper bag he kept in his desk drawer. He’d lectured them all about frugality, but then he showered them with sweets. “I never liked peppermints.”

“But you never told him, did you?”

“No. I gave them to you, instead.” At Adam’s suggestion, as she recalled. Emily narrowed her eyes at her cousin. “So, really, you had no cause to complain. You were hardly cheated.”

His expression troubled, Adam reached out and squeezed her hand. “I didn’t begrudge you the sweets, Emmy. And I don’t begrudge you this. I just . . . I don’t want to see you—”

“Toiling in the fields?”

Adam didn’t return her amusement. “Caught up in some scheme of Grandfather’s. You know how he was. He liked his surprises and his japes.” Glancing over his shoulder at Dr. Braithwaite, he said darkly, “Look at him, sending us off to his old friend Turner without ever letting on that the man’s a nigger. I’d wager he had a good laugh when he put that in the will.”

Looking back, Emily saw Dr. Braithwaite watching them. She twitched her hand away from her cousin’s. “That’s not fair,” she said flatly. “I don’t believe Grandfather ever thought of that. He admired Mr. Turner for his business sense.”

Adam shrugged. “Have it as you will. But you can’t deny the old man liked to make everyone dance to his tune. He yanked us about like puppets.”

He was, Emily suspected, thinking of their grandfather’s opposition to his marriage with Laura, which had been fierce and vocal. “Only for the best,” she protested. “He always meant it for the best, whatever it was.”

Adam made a noise of frustration. “I just don’t want to see you hurt. I know you loved him—I loved him too!—but he was no saint. My father always said there was more to Grandfather’s past than we knew.”

“Whatever it was,” said Emily firmly, stepping away, “it was forty years ago. How can it touch me now?”

Adam looked as though he might say something else, then shrugged. “You’ve always taken your own counsel.”

She’d offended him. Emily tried to make it right, just as she had, long ago, when they had played blindman’s bluff and he’d had to be soothed when she won. “I appreciate your advice, Adam, truly, I do.”

Adam knew her as well as she knew him. “You just won’t take it.”

“No,” she said apologetically. As she watched, he turned again to look at Laura, who was speaking animatedly—animatedly for Laura—to Mr. Davenant. Emily touched his arm. “Would you take some from me?”

“That depends on what it is,” said Adam, already moving away toward Laura and Mr. Davenant. “Ah, Mr. Davenant, shall we?”

Emily caught Dr. Braithwaite’s eye and bit down hard on her lip. Maybe Adam was right. Maybe it wasn’t any of her business. They were husband and wife now, after all. It didn’t matter that she’d kn

own Laura longer and better; it would be a point of pride to Adam not to take her advice, although he’d been glad enough for it during their courtship.

“My dear?” Adam held out his arm to Laura with aggressive courtesy. “If I might help you into the carriage?”

Laura looked slightly bewildered but accepted his help. “It was very fortunate that we came upon Mr. Davenant,” she ventured, as Emily joined her on the seat.

“Oh yes, very fortunate,” echoed Adam.

“Shall I ride alongside?” suggested Mr. Davenant tactfully, positioning himself by Emily’s side of the carriage, well away from Adam and Laura. “Of course, Nathaniel knows the way.”

“Oh?” Emily echoed, looking at Dr. Braithwaite. Hearing him referred to as Nathaniel was like seeing him in his shirtsleeves, an unimaginable invasion of his privacy.

Dr. Braithwaite’s lips tightened at the casual use of his name, but he made no comment.

“Is it far?” inquired Emily, as the coach began to lurch again down the rutted drive.

“Not as the crow flies,” said Mr. Davenant.

“Or by horseback?” suggested Emily. Mr. Davenant rode with the ease of a man who spent most of his time in the saddle.

Mr. Davenant dipped his head in acknowledgment. “My morning ride often takes me out this way.”

“Trespassing?” said Dr. Braithwaite, and Mr. Davenant’s fair face flushed.

“My grandmother likes me to keep an eye, make sure no one’s making trouble. That was before we knew of Miss Dawson’s arrival,” he added, with a courteous bow in Emily’s direction. “As to that, I’ve heard you’ve been making visits to Beckles. What are you doing poaching MacAndrews’s patients, Nat?”

“Healing them,” said Dr. Braithwaite. He propped one ankle against the opposite knee. “I’m surprised he noticed they were missing.”

“Well, when the pest house is empty . . .”

“Pest house?” asked Emily.

“Our . . . infirmary, I guess you’d call it?” Mr. Davenant looked to Dr. Braithwaite for assistance, but the doctor didn’t seem inclined to provide any. “Dr. MacAndrews comes once a week to visit the sick.”

“And if they weren’t sick before his visit . . .” murmured the doctor.

Mr. Davenant gave an airy wave of his crop. “MacAndrews does his best.”

“The man’s a sot,” said Dr. Braithwaite bluntly. “The only thing he knows how to physic is his own thirst.”

“I say, that’s not fair. The man’s been at Beckles longer than I have.”

“So has beriberi,” said Dr. Braithwaite. “That doesn’t mean you want to encourage it to stay.”

All around them, the wilted stalks had given way to tall green cane; the carriage wheels seemed very loud on the smooth surface of the road. “You might have asked before you started making house calls.”

Dr. Braithwaite leaned back against the squabs. “Tugging my forelock and begging permission? The patients I’m treating are all freemen.”

“Yes, in our employ.” Blue eyes met brown. The blue eyes dropped first. Jokingly, Mr. Davenant said, “You might send us a reckoning, at least.”

No answering smile touched Dr. Braithwaite’s lips. “Oh no. This I do on my own account.”

Mr. Davenant’s horse sidled restlessly. “As you will. Your uncle is richer than Midas, isn’t he? I don’t imagine you miss the fee. If you look up ahead, Miss Dawson, you’ll see Beckles.”

“Where? Oh—I see now.” There were no towering gables here, no Jacobean chimney pots. The house was wide and low, large parts of it all but obscured by enormous, flowering shrubs.

Mr. Davenant reined in his horse. “It isn’t as grand as Peverills, but at least the roof still stands.”

“It’s lovely,” said Emily. It was a meringue of a building, stucco gleaming white in the sunshine, capped by a red slate roof, which was, indeed, intact.

Mr. Davenant waited for the coachman to lower the stairs before holding out a hand to help her down. “But rather bland after Peverills?”

“I didn’t say that.” His grip was stronger than she would have expected; she had thought him more scholar than athlete. Emily gave her crumpled skirts a brisk shake as she stepped out onto the brick walk. Ahead of her, a flight of stairs led up to a broad veranda. “It’s just . . . very different.”

“Peverills is one of the oldest houses on the island. They don’t tend to last, you know. Between hurricane and fire . . . Bridgetown’s been rebuilt half a dozen times since I was born, at least.”

“Hurricane?” said Laura as Mr. Davenant handed her out of the carriage.

“You needn’t worry,” Mr. Davenant hastened to reassure her. “Beckles was built to withstand hurricane. Our walls are two feet thick.”

“Not to mention that it isn’t the season for hurricane. You’ll be back in England long before there’s any danger.” Dr. Braithwaite remained seated, making no move to follow them. To Mr. Davenant, he said, “Mrs. Davenant’s carriage shall, I take it, be made available to return my uncle’s guests to Bridgetown?”

Mr. Davenant nodded, seeming relieved. “Certainly. I’ll see your guests safely back to Bridgetown.”

Emily looked from one to the other. “You’re not stopping?”

“I have obligations in town,” said Dr. Braithwaite.

Those obligations hadn’t prevented him from planning to share their picnic at Peverills, only from sitting at table at Beckles.

Emily frowned up at the figure in the carriage, reduced to a dark outline by the angle of the sun. “I hadn’t realized—if it’s inconvenient . . .”

Mr. Davenant offered her an arm. “Don’t distress yourself, Miss Dawson. Our coachman should be delighted to convey you back to town. It isn’t the least trouble.”

It wasn’t their return journey that was distressing her, and Dr. Braithwaite, at least, knew it. He looked at her as though daring her to voice her objections.

But how could she? No one had intimated that Dr. Braithwaite might be unwelcome. She would only embarrass herself and her cousins by pushing the point.

“Thank you,” said Emily in a constrained voice. “And thank you, Dr. Braithwaite, for your escort today.”

Dr. Braithwaite tipped his hat. “Miss Dawson. Mrs. Fenty. Mr. Fenty. Enjoy your luncheon.” To Mr. Davenant, he merely inclined his head.

“Nathaniel—” said Mr. Davenant, but the carriage was already turning in the drive, bearing Dr. Braithwaite away.

“Stiff-necked, isn’t he?” commented Adam lazily.

“I wouldn’t say that. Shall we?” Mr. Davenant gestured toward the stairs. Something winked at them from the veranda, a sudden flash of bright light.

Emily blinked, seeing stars. “Do you know Dr. Braithwaite well?”

They ascended the stairs in silence, the air heady with the scent of flowers and sugar. After a moment, Mr. Davenant said, “Nathaniel used to work at Beckles.”

Laura and Adam were several treads behind them, Adam deliberately keeping Laura to himself. Emily chose her words carefully. “Was that before the implementation of the Slavery Abolition Act?”

“Yes.” Mr. Davenant’s eyes met hers. They were, she noticed, a very pale, clear blue. “Nathaniel was the son of our cooper. We used to play hide-and-seek in the barrels—against strict instructions, I might add. But that was a very long time ago. I doubt either of us would fit in a barrel these days.”

“No,” said Emily. Impossible to imagine Dr. Braithwaite, in his impeccably tailored suit, squirming through the staves of a half-constructed barrel. A slave. “Were you of an age?”

Mr. Davenant paused on the veranda, giving Laura and Adam time to catch up. “Nathaniel is a few years older. I hadn’t any brothers or sisters, you see. My mother . . . well, never mind that. Ah, here we are.”

The front door opened and a maid emerged bearing a tray with four silver cups.

“Lemonade?” said Mr. Davenant proudly.

“But how—?” Laura look

ed up at him as he handed her a silver cup, sweating slightly in the heat.

Mr. Davenant pointed to a metal tube mounted to the railing of the veranda. “They’ll have seen us coming some time since. I’ll wager Sally has already laid extra places at table.”

Emily took a cup, the metal cool beneath her fingers, incised with a coat of arms too faded to make out. “Is that a spyglass?”

“Yes,” said Mr. Davenant, taking a grateful swig of his own drink. “It’s an old planter trick, to welcome one’s guests with the door open and a cold drink at the ready.”

And see what one’s slaves were doing, Emily didn’t doubt. “May I?”

“Go right ahead,” said Mr. Davenant.

The metal was warm to the touch but not hot; the hedges shaded the veranda from the sun. The road leaped out at her and, on it, Dr. Braithwaite in the barouche, making his way back to Bridgetown.

He had shifted to the forward-facing seat, his back to Beckles. Relieved to be done with them? No doubt.

They would not, Emily supposed, see him again, and she found the thought unsettling, although she wasn’t sure why. The sense of a conversation unfinished, perhaps. Or the fear that she hadn’t shown to good advantage—that all of them hadn’t shown to good advantage—and she wanted to set it right.

The polished lacquer winked in the sunlight, disappearing behind the long stalks of cane.

“Don’t keep it all to yourself,” said Adam, and Emily obligingly moved aside. “Ahoy, mateys! I feel quite piratical.”

“When I was a boy,” said Mr. Davenant, taking Emily’s empty cup from her and setting it back on the tray, “I thought my grandmother was omniscient. She knew whenever I was getting into something I shouldn’t.”

“Climbing into the cooper’s barrels?” said Emily. “But I could see only the road.”

“Oh, this is only one of many,” said Mr. Davenant. “There are spyglasses all about the house. I’m sure I haven’t found the half of them. My forebears liked to know what was going on about them. There wasn’t anyone or anything on their land they couldn’t see.”

“How . . . enterprising,” said Emily.

Mr. Davenant looked uncomfortable. “It’s hard to explain how it was. One lived alone out here, surrounded by one’s people. Not that one didn’t trust one’s people, but . . .”

That Summer

That Summer The Mischief of the Mistletoe

The Mischief of the Mistletoe The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla

The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla The Other Daughter

The Other Daughter The Ashford Affair

The Ashford Affair The Lure of the Moonflower

The Lure of the Moonflower The Secret History of the Pink Carnation

The Secret History of the Pink Carnation The Masque of the Black Tulip

The Masque of the Black Tulip The Passion of the Purple Plumeria

The Passion of the Purple Plumeria The English Wife

The English Wife The Garden Intrigue

The Garden Intrigue Ivy and Intrigue: A Very Selwick Christmas

Ivy and Intrigue: A Very Selwick Christmas The Orchid Affair

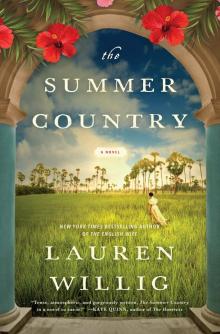

The Orchid Affair The Summer Country

The Summer Country The Betrayal of the Blood Lily

The Betrayal of the Blood Lily The English Wife: A Novel

The English Wife: A Novel Masque of the Black Tulip pc-2

Masque of the Black Tulip pc-2 The Secret History of the Pink Carnation pc-1

The Secret History of the Pink Carnation pc-1 That Summer: A Novel

That Summer: A Novel The Mischief of the Mistletoe: A Pink Carnation Christmas

The Mischief of the Mistletoe: A Pink Carnation Christmas